117 West 90th Street

Maybe right now on 117 West 90th Street in apt 5B, there are 56 years of memories all floating around simultaneously, never disturbing each other, and playing out on a plane I will never see.

For Mercedes Lim (July 24th, 1927 - July 31st, 2022)

I think about my grandma’s house a lot. 117 West 90th. It was a three-bedroom apartment on the Upper West Side, something people would kill for today. The catch was the building she lived in was a project, part of the “Urban Renewal” of the 1960s. The Wise Towers were built in 1963, and as far as I know, my grandmother, grandfather, and their children all moved in within the same year that it opened.

She lived in apartment 5B for 56 years.

My mother lived there for 29 years and remembers it as not only the place where she grew up but the space where everyone convened. Family, friends, and those that found it okay to invite themselves over to watch TV could all be found in apartment 5B. By the time I was old enough to form memories, Grandma was too old to host holidays there but still up to having me and my brother come around on sticky summer days. There were few upsides to being away from my house, its air conditioning, all my toys, and the promised land that was New Jersey suburbia. Her apartment was hot because she never turned on the AC. I was often bored of sitting outside all day long on a bench with her group of elderly female friends, and worst of all, the channel numbers on Time Warner were different than DirectTV, which in reality didn’t matter much because my older brother always controlled the remote.

The benefits were the free city lunch that always came with a nectarine, rainbow-flavored coquito, and the rare instance when we could convince her to get us pizza from Domino's on 89th. I was a fool for passing up a home-cooked meal back then and would do anything for one now, but cheesy bread and chocolate lava cake were a delicacy in my mind.

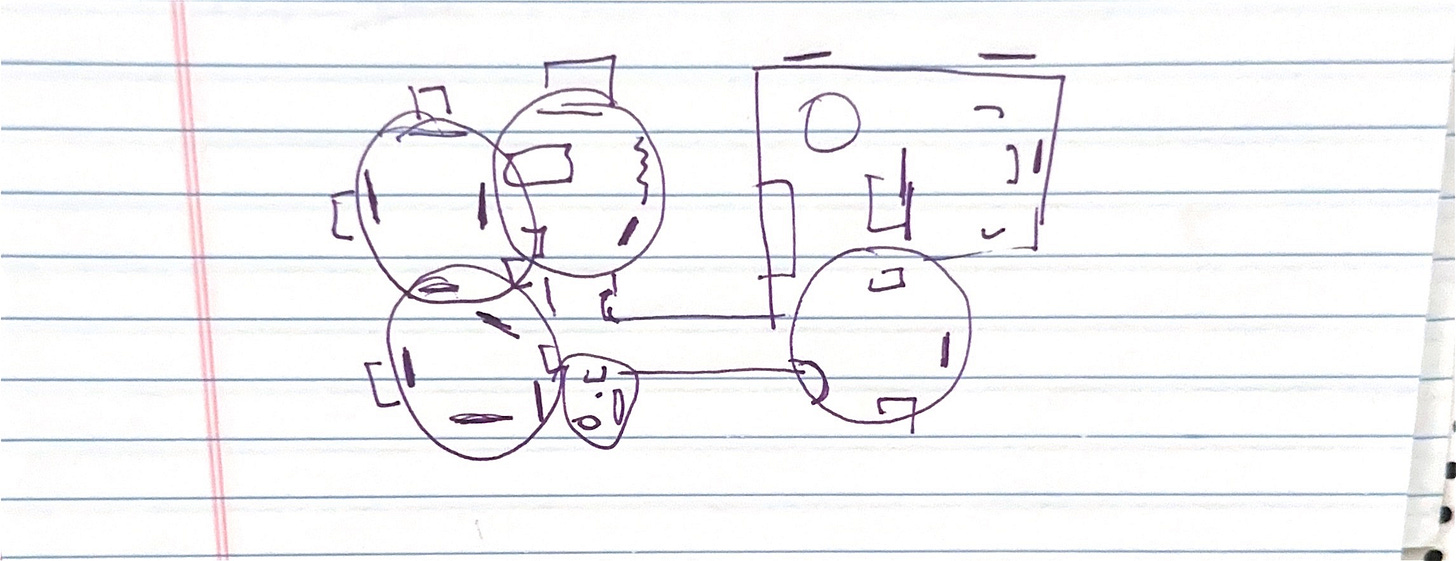

I try to map out the ground plan of my grandma’s home in my head a few times a week. I’m worried that if I don’t, I’ll forget it, and I’ve always been proud of my superhuman ability to remember the most minuscule details of life. I reminisce about the green glass Coca-Cola cups that were all broken by the time I was twelve. How she kept one old bottle of hot sauce for my father to use, and eventually my brother when he was old enough to prove his masculinity by dousing his food in it. Of course, the chuletas and rice never needed it, and even through her constant warnings about how hot sauce was bad for you, the men dared to eat it anyway. I think about the collection of carefully cut-out photos of the children she cared for that hung near the front door. Their loving faces bid her farewell before each journey into the city and served as a warm welcome when she returned home.

Forgetting all I know of her and the home she created threatens to sever what connects my current reality with her past life. Now that she is gone, all I can hold onto are memories. Losing those feels like a threat to our relationship. The final nail in the very literal coffin that separates us. I fear the inevitable forgetting, and even as I fish in my mind for memories to put on paper, I can feel the effects of time and the influence of others complicating what was once so clear. I fear my memories morphing into something hazy and diluted but maybe less heavy on my heart. I have to remember as much as possible, not only for my sake but also to honor the life she designed in apartment 5B over decades. The choices she actively made in decorating and organization give so many details about who she was. What is so hard to come to terms with now, as the dust settles a year after her passing, is the things we spend time building are temporary, especially in a city like New York, and even more so in public housing.

It is strange how places that are so familiar and central to your life can be gone instantly. I can still smell that apartment. The scent of hot canola oil ready to fry chicken, the vanilla musk perfume Grandma made my mom hunt for at Duane Reade's across the city, and even the smell of piss puddles that always seemed to be in the elevator corner. It’s hard to have such defined memories of something you’re no longer welcome to engage with. To cope with that, I challenge myself to remember all the little things we tend to forget about spaces we spend so much time in. Those memories, as mundane as they may seem, hold answers and pose questions I’m not closer to answering.

Maintaining a collective memory of her life is crucial, but the personal notes I have of her, I am protective of. I want to remember her in a particular way, one that selfishly suits me, but also try and figure out who she truly was outside of my scope and before anyone still alive could even create memories. So, I wonder, is it wrong to hope for her, dream in her absence? Assume feelings that never existed. Imagine scenarios of struggle, but also romanticize moments when it feels right. To search only for evidence that supports my narrative of her as a hero, as one of the strongest people I've had the pleasure of knowing. The more I learn about her, the more complicated it is to take these actions without an ethical dilemma. Her life deserves nuance, and I can't judge her choices. To find any real understanding of her means abandoning who I wish she was and accepting I may never know the truth. There are good things and bad things I've learned that I will never understand and simply try to accept. Part of this is letting go of the idea that there needs to be more. More things that make her special, more things that make her story worth telling. More hidden answers that feed a narrative I've created when there might not be any.

The history I know of my grandma’s life from her early years, or the time before my mother has memories, is spotty. They’re mostly second-hand stories my mom has passed on through the years. Attempting to piece together my grandmother’s life has always felt daunting, mainly because I'm unclear on dates or her age when certain events took place, and she seemed to be a very private person. I’d love to write her story in depth another time when I can do her more justice, but here’s what I’m certain of. Grandma was born Mercedes Hernandez in Manati, Puerto Rico, on July 24th, 1927. She was the second of seven children. During her youth, much of the labor of family rearing was left up to her as the eldest daughter. In her twenties, she ventured alone to New York City. Leaving one island for another, she settled in with a Titi who had already begun a life on the mainland.

From what I've heard, these first few years in the city were not welcoming or enjoyable, and eventually, after pressure from her family, she married her first husband and had a son at 25 years old. She was ultimately followed by her mother and six other siblings and had to resume the caretaker role. She cooked, cleaned, and financially supported her family. Her first marriage ended in divorce. I'm not sure why, and even if I was, I'm sure my family doesn't want me airing all of our dirty laundry, at least not yet. For work, she sewed garments in factories and eventually met my grandfather. I'm not sure when they got married, but they did have two children, and in 1963, they would set up a home at 117 West 90th. Of course, this is an oversimplification of all of the positive and negative moments of the life that she led. The anecdotes shared with me give snapshots of moments that were funny, serious, or sometimes just sad, but they are far from a clear timeline of her experiences that I can break down here. But what I’ve gathered from the information I do have is that Grandma was indeed human. She made mistakes, but she was always reliable. She had lapses in judgment but was still beloved. Grandma was a rock for many, even if few returned the favor.

As the youngest of her grandchildren, though I have special memories and interactions I’ll always hold close to my heart, I still feel slighted by time. My cousins remember her younger, stronger, and perhaps in a way that was more authentic to herself. They had many good years with her where she could still do so much. My oldest cousin was born in 1975. Grandma would've been turning 48, and my mom was only 14. I sometimes resent that I had very few "good" years and that I was there with my mother watching and accepting the deteriorating reality of aging. As I struggle with knowing her authentically, I've tried to accept that she'll only know me as a child. Maybe in her mind, I'm still her cachetona or the little girl who visited 117 West 90th with her 3rd-grade Girl Scout Troop. She didn't see me graduate college, she'll never see me get married, and she’ll never know who I will become.

But there is promise in this newness. This youth lets me hold onto things others have forgotten with time. I find comfort in returning to the items, the keepsakes, the mundane objects that made up her home and kept her functioning every day. I feel excitement in this ability to remind my mom of something small like the mint green plastic serrated knife she used to cut up the salad we shared over dinner. Some of the items I recall are strange, like the hobo statute that always sat in the corner of the living room, its eyes constantly begging. Others hilarious, like the shrine to my mother that hung on the wall, two photos of her graduating high school and college, respectively, on either side of a gigantic 24x36 inch print of her in all white, not from her wedding day, but from her communion. And some of them were beautiful, like the drapes she would make by hand for each set of windows, which were often trimmed with lengths of shiny beads. I find it bittersweet when asking my mom questions about objects and moments she may have forgotten, but our conversations are what will keep her memory alive. She'll share the little stories and things that remind her of her mother. I'm sentimental, so I can't help but cry, but I look forward to a time when I find only joy in memory.

I’m stuck at the cross-section of memory, reality, and the impermanence of our existence. Throughout my grief, there have always been moments of remembrance, things that I know for sure my grandmother did or enjoyed. As I've been forced to reflect on these memories, I have few places to ask for more information, to seek clarity on her motivations and inspiration. To confirm that my memory is part of a shared reality. There are no physical spaces to go back to and look for clues. Those spaces are occupied by others who will go on to form their memories on top of the already existing ones that linger in apartment 5B like a weird memory lasagna. It feels wrong to superimpose my belief and assumptions about why she made difficult choices. Her life as a Puerto Rican immigrant in New York City wasn't easy, and neither was the decades she spent on the archipelago with the responsibilities of an adult as a child.

As a kid, and still to this day, I like to watch the home video tapes my parents recorded. As I've already shared, I'm sentimental, and tapes from before I was born can make me cry. They're all still, inconveniently, on video cassettes, and I have to take out the 5-pound camcorder to play them.

I always liked to think that the moments those tapes highlighted were constantly happening around me in an alternate universe. I found it fascinating to see my house as it was 20 years ago, where the furniture was, the hiding spots I gravitated to as a child, and everything that is still the same. Similarly to an out-of-body experience, these clips would be moving around me all at once, even if I can't see them. Maybe all memories work that way, not just the ones caught on film. Maybe right now on 117 West 90th Street in apt 5B, there are 56 years of memories all floating around simultaneously, never disturbing each other, and playing out on a plane I will never see.

As I've said, memories are constantly changing, and some of the ones that keep me up at night take place during the last years of her life.

Even after leaving the apartment for a nursing home, my grandma would ask to go home. She would quite literally shout, "Take me out, I want to go home. 117 West 90th," to no one in particular. She left this open, in hopes that any reasonable person who heard it would rescue her. I hated this. Some of my family had to laugh at it; I knew to keep from crying. But I hated to hear her strained voice calling for something that was gone. It broke my heart. After 56 years of living there, she was dealing with an even more complex loss than I am struggling to process here. The sudden loss of a space that is the center of so many memories. Whether good or bad, they took place in apartment 5B, and nothing can change that. Parts of her memory were confused, simply a side effect of old age. She would forget my cousin had a baby and be unsure of what day of the week or year we were in. I blame that on her lack of access to information and interaction during the pandemic, but there were also things she never forgot. She always asked for her girls. Always, even if they didn’t ask for her.

Home is complicated for lots of people. I wondered if Grandma considered Puerto Rico home, but it was clear that home was 117 West 90th.

One of the greatest memories I have of her developed after she had left. Something my superhuman abilities had forgotten was all the translating I had asked her to do. While in the nursing home, I asked her what "Guararé" meant. I spoke up to make sure she heard me and had my mom ask as well, just to be safe. When someone has "Guararé," they're annoyed or frustrated, a passive-aggressive energy. I wanted to know because my latest hyper fixation was a song from Ray Barretto’s Album “Barretto.” The first track was entitled “Guararé," and I was trying to figure out what they were saying. She helped the story make sense, and I could go on enjoying it with clarity. Flash forward a few months later, the song is still in heavy rotation when I aux in my mom's car. As I sang along, I saw her smiling to herself. "This song reminds me of Grandma," she said. I don't respond, already preparing myself to silently cry. I've never been good at speaking through tears. "You asked her what it meant, and she translated it for you." I had forgotten all about that moment that had taken place when conversations weren't fluid, and Grandma was mostly quiet.

I love that song.

I have a hard time listening to it now. I can’t help but get choked up.

I hear her in music, I see her in the Entenmann's coffee cake at the supermarket, and I most definitely see her when I've gone out of my way to visit the 117 West 90th. Even though I no longer can go in, I stare at the bench where she sat all those years. The company she had dwindled over time until it was just her, sitting contently next to the bench on her walker.

Thank you for sharing this tender story ❤️

Beautifully written. This story made me cry as it reminded me of the life I knew of my own late grandmother. Thank you for sharing 💕